The Indian Constitution guarantees equality as a fundamental right under Article 14. However, equality does not mean that the law must treat every individual in exactly the same manner in all situations. In a country as socially, economically, and culturally diverse as India, absolute equality is neither practical nor desirable. To address this complexity, Indian constitutional jurisprudence has developed the doctrine of reasonable classification, which allows the State to classify individuals or groups for legislative purposes, provided such classification meets certain constitutional standards.

The doctrine of reasonable classification plays a crucial role in balancing the principle of equality with the practical needs of governance. This article provides a comprehensive explanation of the doctrine, its origin, judicial interpretation, tests, limitations, and contemporary relevance under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

Meaning and Scope of Equality under Article 14

Article 14 of the Constitution states:

“The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.”

This provision contains two important concepts:

- Equality before law – a negative concept that implies the absence of any special privileges and the equal subjection of all persons to ordinary law.

- Equal protection of laws – a positive concept that requires the State to treat equals equally and unequals differently.

The second concept forms the constitutional foundation of the doctrine of reasonable classification. It recognizes that treating unequals equally may itself result in injustice. Therefore, reasonable classification is permitted as long as it does not result in discrimination that is arbitrary or irrational.

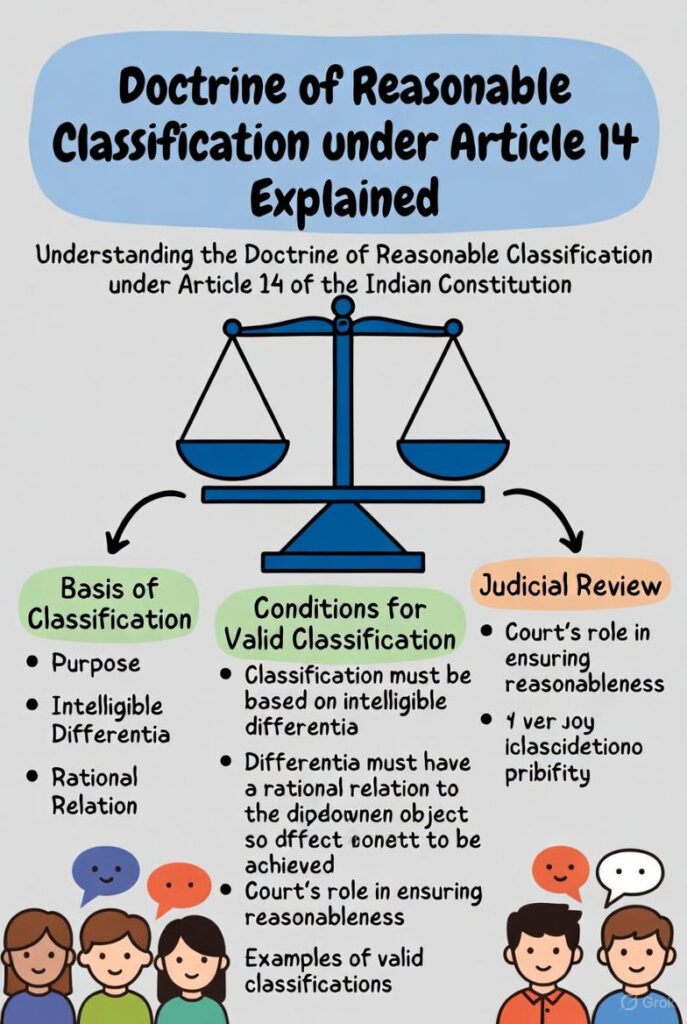

What is the Doctrine of Reasonable Classification?

The doctrine of reasonable classification refers to a legal principle that allows the State to classify individuals, groups, or situations for the purpose of legislation, provided that such classification is reasonable, non-arbitrary, and based on an intelligible basis.

In simple terms, the doctrine of reasonable classification permits differential treatment under law if:

- The classification is based on real and substantial differences.

- The classification has a rational relationship with the objective sought to be achieved by the law.

The doctrine ensures that Article 14 does not prohibit all forms of classification, but only those classifications that are arbitrary, artificial, or discriminatory in nature.

Origin and Evolution of the Doctrine of Reasonable Classification

The doctrine of reasonable classification in India has evolved through judicial interpretation of Article 14. While the idea of equality was inspired by the English concept of rule of law and the American concept of equal protection, Indian courts developed their own nuanced approach to equality.

In the early years after independence, the Supreme Court adopted a formal and classification-based approach to Article 14. The Court recognized that legislative classification is inevitable in a welfare State and that the Constitution does not demand absolute equality.

Over time, the doctrine of reasonable classification became the primary tool used by courts to assess the constitutionality of laws challenged under Article 14. However, with changing social realities, the Court expanded the interpretation of equality to include protection against arbitrariness, thereby complementing the doctrine of reasonable classification.

Test of Reasonable Classification

For a classification to be constitutionally valid under Article 14, it must satisfy a well-established two-fold test. This test lies at the heart of the doctrine of reasonable classification.

1. Intelligible Differentia

The first requirement is that the classification must be founded on an intelligible differentia. This means that there must be a clear and understandable distinction between those who are included in the class and those who are excluded from it.

The basis of classification may be:

- Age

- Gender

- Occupation

- Economic status

- Educational qualification

- Nature of activity

However, the basis must not be arbitrary or vague. The intelligible differentia should be real and substantial, not artificial or illusory.

2. Rational Nexus

The second requirement is that the intelligible differentia must have a rational nexus with the object sought to be achieved by the law. In other words, there must be a reasonable connection between the classification and the legislative objective.

If the classification has no logical relationship with the purpose of the law, it will fail the test of the doctrine of reasonable classification and be struck down as unconstitutional.

Both conditions must be satisfied simultaneously. Failure to meet either condition renders the classification invalid under Article 14.

Landmark Judicial Pronouncements

State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952)

This case was one of the earliest decisions interpreting Article 14. The Supreme Court struck down a law that gave unguided discretion to the executive to refer cases to special courts. The Court held that arbitrary selection without reasonable classification violated Article 14.

This judgment laid the groundwork for the doctrine of reasonable classification by emphasizing that classification must be based on clear principles.

Shri Ram Krishna Dalmia v. Justice S.R. Tendolkar (1958)

This case is considered the most authoritative judgment on the doctrine of reasonable classification. The Supreme Court clearly formulated the two-fold test of intelligible differentia and rational nexus.

The Court also observed that there is always a presumption in favour of the constitutionality of a law, and the burden lies on the person challenging the classification to prove its unreasonableness.

Saurabh Chaudri v. Union of India (2003)

In this case, the Supreme Court upheld reservation in postgraduate medical courses based on domicile. The Court held that the classification had a rational nexus with the objective of promoting medical education in underserved regions.

The judgment reaffirmed the continuing relevance of the doctrine of reasonable classification in modern constitutional law.

E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974)

This case marked a significant shift in the interpretation of Article 14. The Supreme Court held that equality is antithetical to arbitrariness and that arbitrary State action violates Article 14 even if no classification is involved.

While this case expanded the scope of Article 14, it did not replace the doctrine of reasonable classification. Instead, it supplemented it by introducing the concept of non-arbitrariness.

Doctrine of Reasonable Classification and Doctrine of Arbitrariness

Traditionally, Article 14 challenges were examined only through the lens of classification. However, judicial interpretation evolved to recognize that even a law without classification can be unconstitutional if it is arbitrary.

The doctrine of reasonable classification focuses on the structure of classification, whereas the doctrine of arbitrariness focuses on the fairness of State action.

Today, courts apply both doctrines together. A law may be struck down if:

- The classification is unreasonable, or

- The law is arbitrary, capricious, or lacks fairness

This integrated approach ensures that equality under Article 14 remains dynamic and meaningful.

When Classification Becomes Unreasonable

Not all classifications pass constitutional scrutiny. Classification becomes unreasonable in the following situations:

Over-inclusive Classification

When a law includes persons who have no rational connection with the objective of the law.

Under-inclusive Classification

When a law excludes persons who should logically fall within the classification.

Arbitrary or Artificial Classification

When the basis of classification is vague, irrational, or unrelated to the legislative purpose.

In such cases, the doctrine of reasonable classification fails, and the law is liable to be struck down under Article 14.

Contemporary Applications of the Doctrine

The doctrine of reasonable classification continues to play a vital role in contemporary constitutional adjudication.

Reservation Policies

Affirmative action based on caste, class, or economic criteria is tested on the principles of reasonable classification to ensure social justice while maintaining constitutional balance.

Taxation Laws

Different tax rates for different categories of individuals or businesses are justified using the doctrine of reasonable classification.

Welfare Legislation

Schemes targeting specific vulnerable groups such as women, children, senior citizens, or persons with disabilities rely on reasonable classification.

Service and Employment Laws

Classification based on educational qualifications, experience, or nature of employment is frequently upheld when it satisfies the constitutional test.

Criticism of the Doctrine of Reasonable Classification

Despite its importance, the doctrine of reasonable classification has faced criticism from scholars and jurists.

Some argue that excessive reliance on classification gives courts too much discretion, leading to inconsistent outcomes. Others believe that the doctrine may be misused to justify discriminatory laws under the guise of reasonableness.

The growing emphasis on arbitrariness has addressed some of these concerns by shifting focus from formal classification to substantive fairness.

Importance of the Doctrine in Indian Constitutional Law

The doctrine of reasonable classification is essential for maintaining a balance between equality and governance. It allows the State to address social and economic inequalities while ensuring that legislative discretion is exercised within constitutional limits.

Without this doctrine, many welfare laws and reformative measures would be impossible to implement. At the same time, judicial scrutiny under Article 14 ensures that classification does not become a tool for discrimination.

Practical Examples of Reasonable and Unreasonable Classification

A valid classification example would be providing senior citizen benefits based on age, as age has a rational nexus with vulnerability and need.

An invalid classification example would be granting benefits to individuals based solely on arbitrary characteristics unrelated to the objective of the law.

Such examples demonstrate how the doctrine of reasonable classification operates in real-life situations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the doctrine of reasonable classification an exception to Article 14?

No, it is not an exception but an integral part of the right to equality. It explains how equality should be applied in practice.

Can classification be based on religion or caste?

Such classification must satisfy strict scrutiny and have a strong constitutional justification. Arbitrary classification on these grounds is prohibited.

Is the doctrine still relevant today?

Yes, the doctrine of reasonable classification remains highly relevant and is frequently applied by courts alongside the doctrine of arbitrariness.

Conclusion

The doctrine of reasonable classification is a cornerstone of Indian constitutional law. It ensures that the promise of equality under Article 14 is not reduced to a rigid formula but remains flexible enough to accommodate social realities. By insisting on intelligible differentia and rational nexus, the doctrine protects individuals from arbitrary discrimination while empowering the State to enact meaningful legislation.

In a dynamic constitutional democracy like India, the doctrine of reasonable classification continues to evolve, reflecting the balance between fairness, justice, and governance.